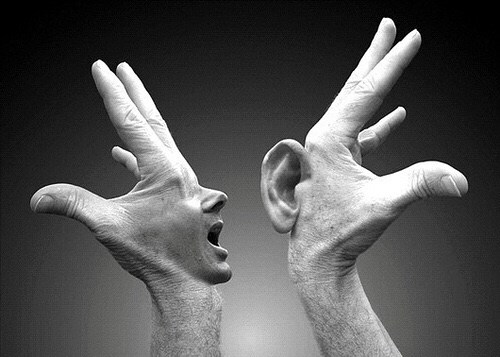

“HALF OF US ARE BLIND, FEW OF US FEEL, AND WE ARE ALL DEAF”- SIR WILLIAM OSLER

In my personal experience, prior to reporting to a physician many patients prepare themselves for their encounter with the doctor. They rehearse and even write down their side of the story, in hopes of giving full information about their problem, to stir up their doctor to make the best decision about their health. While reading some of these detailed notes, either handed over to me personally or mailed to me after the consultation, it seems to me we unreasonably accuse them of overloading us with unnecessary and irrelevant information. To be fair to patients, such criticism is unwarranted, as they are not equipped to filter out irrelevant information, we are. When patients do not get the opportunity of a detailed conversation, they are disquieted and even malcontented with their visit- and their physician.

Few of us have the aptitude to encourage and invite our patients to talk ad lib. Our personal experiences of having to ruck through the hordes of patients waiting to see us, their “select physician,” all of them with hopes of telling us their elaborate medical tales of woe, can take a high toll at times. High volumes, and not enough time in the day can turn busy doctors irascible, forcing them to zip through their consultations. Perhaps, this is one of the reasons many of our patients walk out from the doctor’s clinic feeling dissatisfied, still filled with plenty of unanswered questions. I believe many suspect that the opinion their doctor has just given is based on their doctor’s intuition, but is devoid of totality. We listened, but did not take the time to really hear. Patients are also quick to recognize our active listening habits, particularly so when their consultation time is encroached upon by multitasking or the cell phone. What matter the most to our patients, is the quality of conversation and not the time.

Effective patient-doctor communication is “relationship centered”, wherein a long-term relationship with the physician yields durable confidence in him or her, opening patients to share everything related (or unrelated) to their current problem. Like many doctors, I too have had very pleasant experiences of several patients following me, even after 30-40 years of my association with them. They consult me even for conditions their family members and friends suffer, totally unrelated to my specialty. I treasure these longtime bonds of trust. Today, patients have recognized that they are not passive recipients, but that they have the right to make informed decisions about their healthcare. Nowadays, they have the ability to resist the power, of the expertise and social authority of their doctors. Having said this, I also know that they sometimes make poor choices, despite the advice of their physician.

I now present two representative, real life situations I encountered during my career, to illustrate why listening to your patients is the most vital part of the practice of medicine. The first case will exemplify how listening to the story of a patient helped me in solving a complex diagnostic problem. In the second case, you will learn how I later felt ashamed after my encounter with one patient, because I had jumped straight to investigation, before getting a detailed history from him and breaking golden rule of “listen-examine-investigate.”

Case 1

Mr. X, a young state level athlete was referred to me, complaining of intermittent blood in his urine for the past several years. This patient was very anxious, because it affected his performance adversely. Prior to his visit with me, he had undergone a series of consultations, multiple non-invasive, and invasive investigations. After one colleague from our team had spent significant time with him in the clinic, I initially felt that I had nothing additional to offer. Since I had no brighter idea, I decided to hear him out for the second time, and invited him to my chamber. We talked at length about his professional and personal life, as well as the chronology of his problem. During our long conversation, I got a significant lead about his issue, which was that he bleeds only after he had run beyond 8000 meters. This one simple overlooked clue in his history solved my problem, and the subsequent course of action was straightforward: Since all other possible causes of bleeding had already been ruled out, we could establish the diagnosis of Athlete’s Hematuria, which was actually inconsequential and self limiting. He was reassured that he did not have a serious condition, and was advised to limit his runs to below the 8000-meter threshold. My last follow up consultation with him was several years ago. He told me that he was happy, because his worrisome bleeding did not recur.

Case 2

One routine day, I was called to the endoscopy suite to seek my urgent opinion on a patient a resident was performing endoscopy for. The gentleman was having a burning sensation while voiding, and had blood in his urine. I had a quick look at his urinary bladder and urethra and found that he had multiple tiny concretions in his entire urethra end to end. I concede I had never seen this condition before. I had no time to learn full information about this patient.. After recording these findings, We then decided to talk to the patient to learn more about him, and his problem. We learnt that he was a Yogi, and had performed yogic kriyas daily for over the past 20 years. His Yogic regimen included cleaning his body through all of its natural orifices every morning, comprising: Neti (Cleaning of nose, throat and sinuses), Dhoti (cleaning of the food pipe), Kunjal(stomach), and Enema (for clearing rectum and large intestine). His routine also included urethral catheterization every morning, to empty his bladder. Because of the daily catheterization for 20 years, the entire urethra had formed small concretions. We concluded that he did not need any treatment at that point in time, but strongly recommended discontinuing urethral catheterization.

Medicine is an art whose magic and creative ability have long been recognized as residing in the interpersonal aspects of patient-physician relationship.Realizing the fact that medical students do not enter the portal of medical school with excellent communication skills, King George’s Medical University, Lucknow was perhaps the first medical institution in India used to have a course called “The Art of Listening. ” It was designed for the new entrants in 2003, apprising them of the importance of good doctor-patient communication. This course helped them to discover, learn and practice these skills.

As physicians today, we also need to consider the emotional and physical trauma of the medical education process, and the ever-increasing role medical technology now demands. I find this even more so during the formative years of clinical training. These demands play an active role in setting a young doctor’s personal “default button,” suppressing empathy and encouraging robot like attitudes. Despite my advocacy of robotic surgery, there is no benefit to physicians or their patients for robotic consultations. We must make sure to listen with empathy to each and every one.

“The patient will never care how much you know, until they know how much you care.” Terry Canale, Orthopedic Surgeon

Mahendra Bhandari MD, MBA

drmbhandari.com